Immigrant’s stories for his grandchildren

Immigrant’s Stories work currently showing at the historic Mentzendorff Museum in Central Riga, Latvia, from May until end of August 2025.

Built in 1695 as a home for a wealthy German glassworker in Riga, the gallery is on the fourth floor.

It took five of us the entire day to hang the 36 images which are printed on both art paper and fabric.

Most of the Immigrant’s Stories images and text found in the show are included here.

Why do I cry in Latvia?

My parents fled certain death when the Soviets invaded Latvia.

Oh, the stories. Burying valuables in the forest, leaving home in a horse drawn cart,

dodging bombs and bullets for months, searching for food and shelter each day.

How much of that trauma is passed on to their children, my sister and I?

I was born in a displaced persons’ camp. Immigrated to the United States.

That first day of school, I learned my very first English word: pencil.

I so desperately wanted to become American but still had to go to Saturday Latvian school.

How much of those experiences shape me? Insecure? Shy?

In my thirties, I finally went to Latvia. I cried. No, I sobbed. My whole body shook.

I was born without a home. Walking on Latvian soil felt like returning home. A deep home.

And our mysterious ancient family roots trace back in Latvia to at least the 1700s.

How much of that is part of my deep unconscious memory?

So I create images and recall stories to help me understand the source of those tears.

To help me understand how ancestors and culture make me the composite I am today.

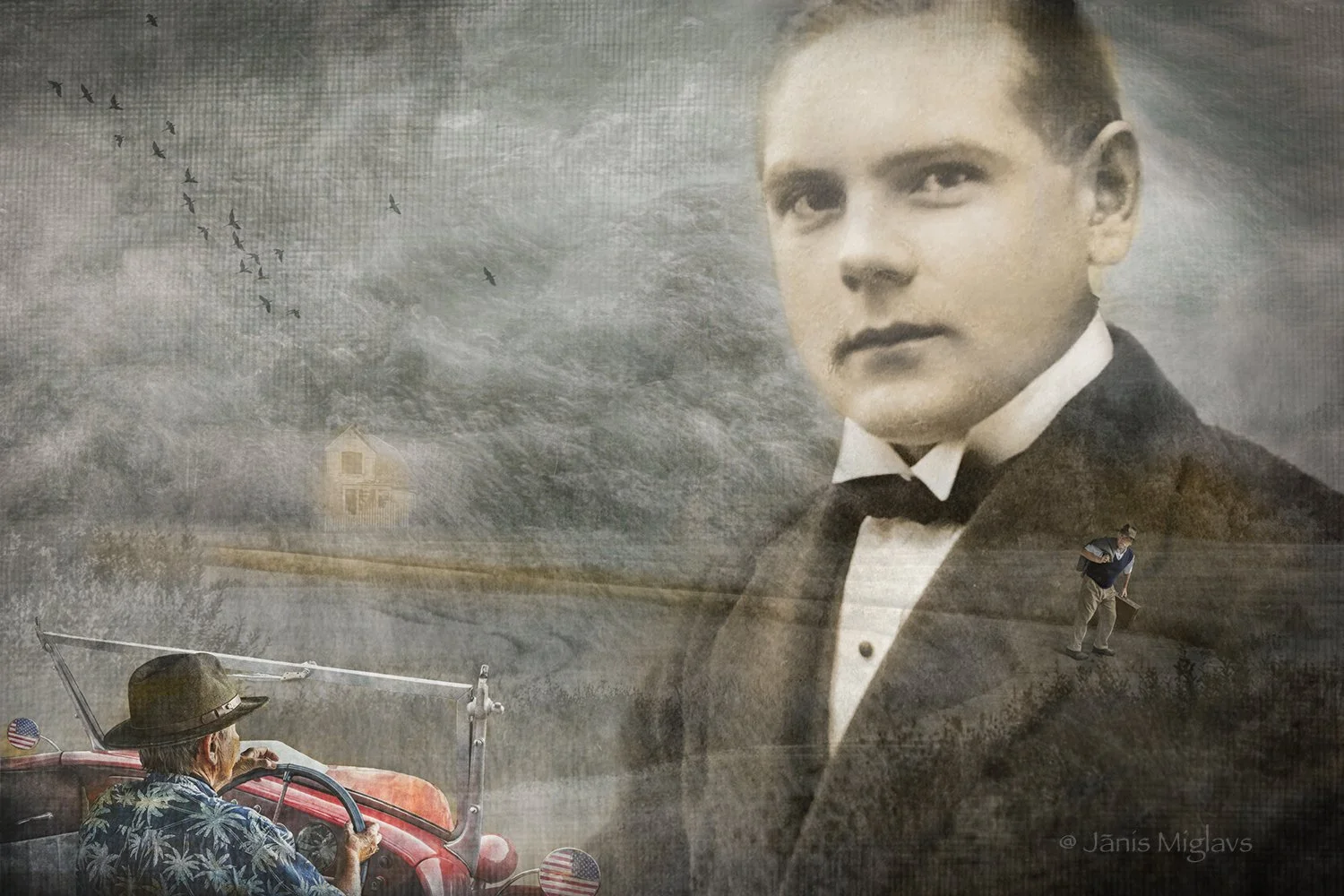

What was that call my heart heard?

The Immigrant begins his journey of discovery.

But what was that stirring in my heart? What did it hear? Why did I need to undertake a pilgrimage to unearth deep roots, to meet relatives I didn't know, to revisit our family farm my parents fled 30 years earlier. Taking the first footsteps to going home.

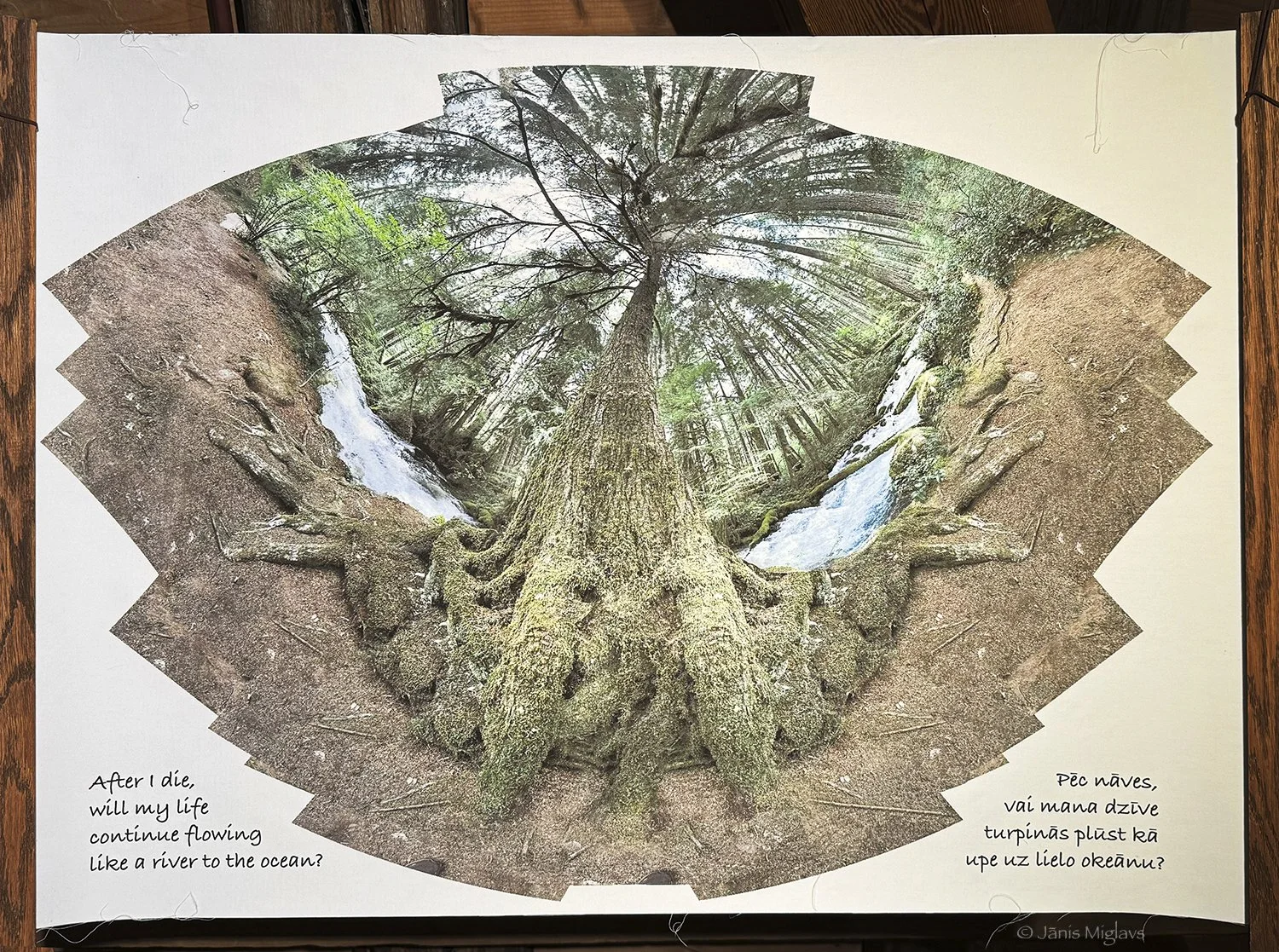

Seeking roots the eye cannot see.

Namnieki property near Vilpulka, Latvia

Walking the forest surrounding our family farm, I reflected on research telling us that those pine and birch have tiny root connections—mycorrhizal networks—extending between them.

This way one tree can transfer resources and communicate below ground to another. Some scientists even argue that trees can cooperate, with the older trees passing resources to seedlings or actually providing information like an approaching beetle infestation, much as a parent might.

Could it be that somehow there are invisible roots connecting me to a forest of mysterious family ancestors dating back to at least the 1700s? What kind of information did those ancients pass on to me through DNA?

Could my deep Homeland feelings be ancestral memories? Information passed through some invisible network?

Every journey has roadblocks

Displaced persons’ camp, Itzahoe, Germany

Emerging from a forest of unknown infant memories.

Mom and dad told me I spent my infant years in two displaced persons’ camps in Germany, Itzaho and Eutin. Looking at photos of DP camps, a gentile wind whispers through a dark forest of memory, stirring something untouchable deep inside. But not a single picture or word is visible in my memory album. Yea, something about the brain’s hippocampus not being developed enough to process the pictures of life.

Yet, surely those memory mystery years left inky fingerprints on me.

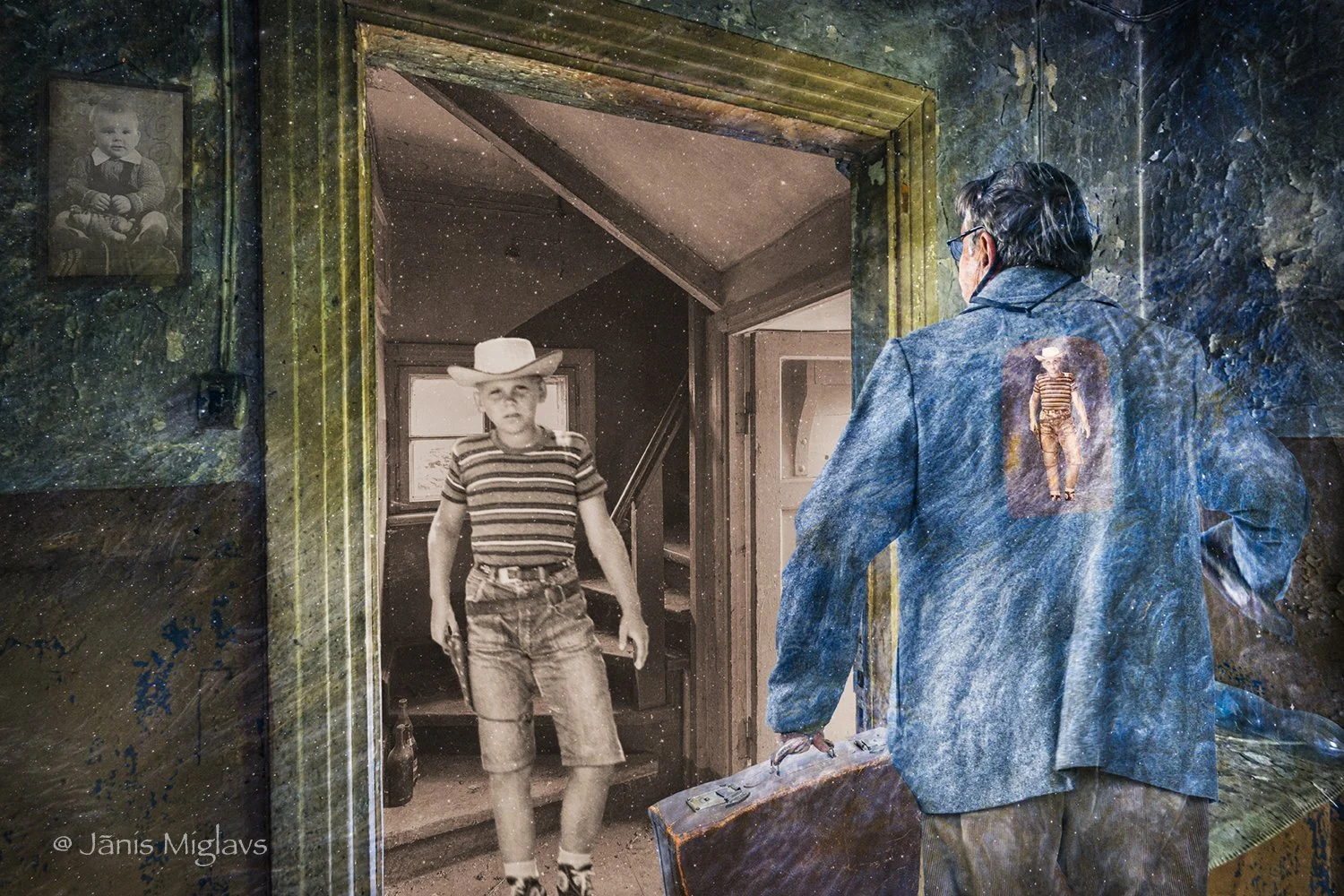

The Immigrant enters the ruins of past memory

Old abandoned house near Namniekos, our family farm 1989-2025

Especially the first trips to Latvia, I didn’t know what I was looking for. Just searching for someone or something that was singing to me. What was it?

Touching a past memory

Immigrant reaching for a past memory of his parents in Latvia.

Where to look for those roots the eye cannot see

Ipiķi school house near Rūjiena, Latvia 2022 - 2023

How much do my mysterious family ancestors affect the inner forest of who I am today?

The more I rummage through the rich soil of my ancestral compost pile, the more I wonder if there are not invisible roots transferring information through DNA? Could they help form who I am today?

Could my deep emotional Homeland feelings simply be ancestral memories?

Thank you, Mom

Thank you, Dad

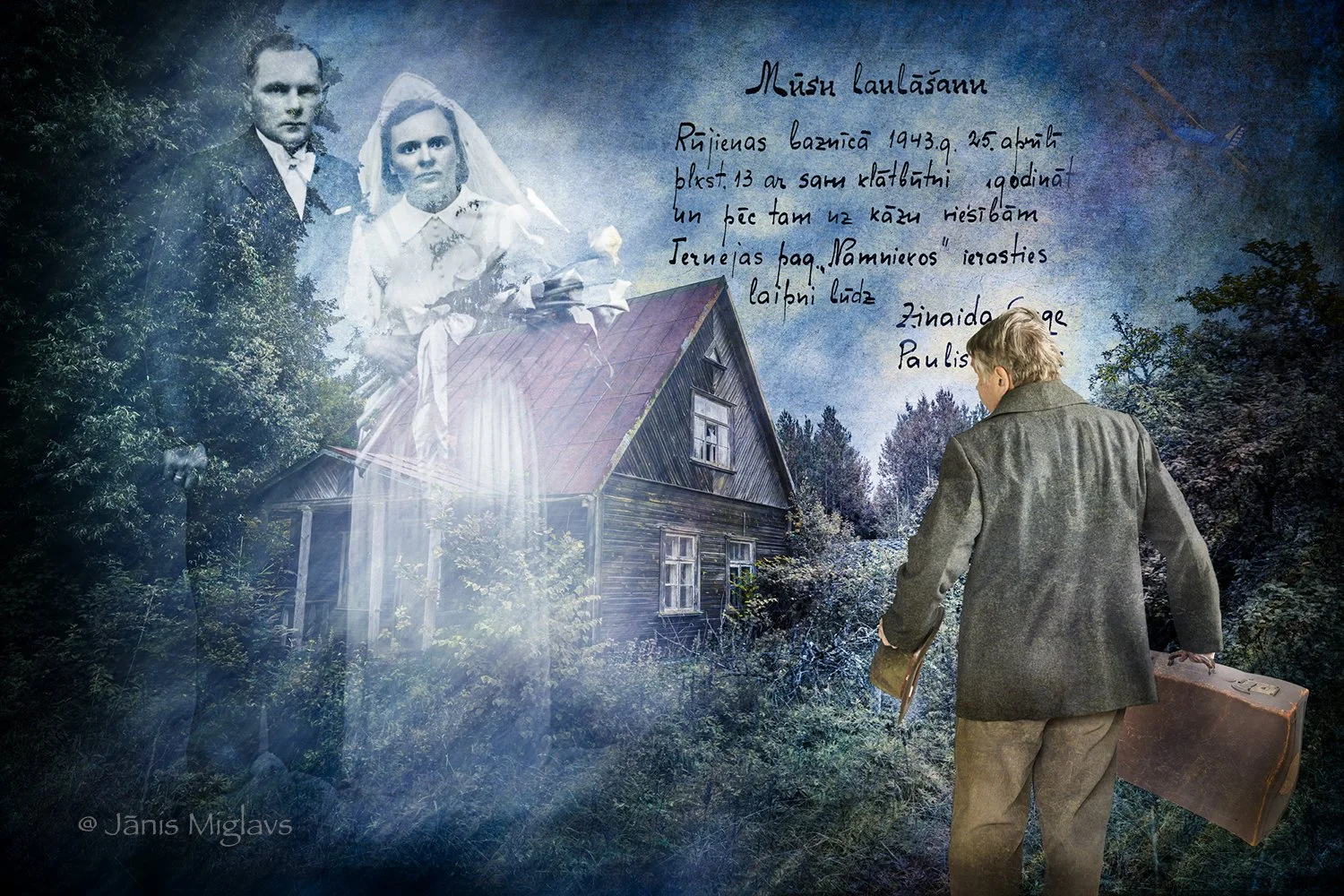

The wedding

Rūjienā, Latvia 1943

Mom hand wrote their wedding invitations. One year after the wedding, they fled Latvia, leaving their home, farm, lifestyle, belongings and country. Carrying only memories.

The escape

Vilpulka, Latvia 1944

Paul married Zinaida in Rūjiena’s white Saint Bartholomew church in the Spring of 1943. One year later, they fled for their lives.

The Soviet army had invaded again. And they considered Paul an enemy of the state for speaking out against them.

Artillery exploded in the distance. One of those shells killed Paul’s brother, the uncle I never would meet.

Paul and Zina huddled around the wooden radio for news about the battle front. They already had packed warm clothes, a few pots and sacs of food in the horse drawn cart. Hitched a cow to the back. Buried valuables in the forest. “Oh, what else can we fit in,” asked Zina.

When the Soviets reached Rūjiena, it was time to flee. They would retreat with the Nazis. Leave their farm, country, culture, their known lives behind. But for how long?

They followed the retreating German army. The Soviets chased like hungry wolves with bombs and tanks. Paul and Zina were not alone in their exodus. Some 134,000 other Latvians fled.

Those newly weds, Paul and Zina, are my parents. I was born during their six-year escape.

It can’t be that bad

Vilpulka village, Latvia 1991-1994

In the early days of Latvian independence, I visited 71-year old Velta in her dark Vilpulka apartment. I stared at her hands. Big. Gnarled. Deeply etched by soul-breaking hardships that words surely cannot touch.

Velta grew up with dreams, hopes and a future with husband, Voldemārs, on their little farm, just a stone’s throw from my parents’ place. Latvia was a free country then.

When Stalin’s troops swept Velta’s homeland for the second time, Velta and Voldemārs decided to flee, along with my parents and some 130,000 other Latvians.

During that exodus, 24-year old Velta, my mother’s best friend, and Voldemārs got as far as her sister’s home. Her sister and husband decided not to flee. So Velta had to choose between family and freedom.

“It can’t be that bad,” Velta tearfully told her husband. They chose family. Turned their horse- drawn cart around and returned to their farm, Tirani. Life seemed manageable.

Until, at sunrise, armed men pounded on the door. Dragged Voldemār and pregant Velta away, the front of her apron still dusted from making morning bread. Loaded onto railroad cattle cars, they—along with some 41,000 other Latvians—were deemed “Traitors of the Soviet cause.” Off to the Siberian Gulag.

In the frozen wilderness their infant son died. That same winter a neighbor’s bull suffocated when its nose clogged shut by its own frozen breath. After eight years, the family returned home to live in a Soviet Latvia.

Velta rubbed her eyes, sighing, “Even to this day, I don’t know what my crime was.”

As I write this in mid-March 2025, I can’t help but wonder how many Americans today are thinking (or hoping), “It can’t be that bad,” after electing a convicted criminal who refused to give up power when he lost his earlier election. And he states that he wants to be a dictator.

Ask Velta if “it can’t be that bad”.

Hope

West Coast, United States 1950

After 6 years of escape, the Miglavs family heads for a new home: America. Carrying in their hearts a hope for the future.

American lessons

Napa, California 4th grade

As a kid, I just wanted to become American. Just fit in. Certainly not speak Latvian in front of my friends. And quietly resented mom dragging my sister and I to Saturday Latvian school.

To me, being American meant becoming an American cowboy. Play cowboys and Indians. Build forts. Shoot guns.

All of us guys in the neighborhood had BB guns that shot little round copper balls. At first, we just shot at small paper targets or empty sauerkraut cans.

Then, maybe in the fourth grade, I went hunting in our backyard. I shot a red-breasted robin sitting in the persimmon tree. Bam. A puff of feathers flew into the air. The bird tumbled to the ground. It just laid there, blankly staring at me with empty eyes.

What I had done? Then some silent enormity overwhelmed me. I had killed something. Just for fun. I started to cry. Really, really cry. I felt like the universe or something bigger than me was watching.

Throwing down the gun, still crying, I ran a mile from our house to downtown Napa searching for my grandmother. I had to tell, maybe confess, to someone. Grandmother “Jepu” was a nurturing person. I finally found her just outside the Woolworth store on First Street. She listened. I don’t remember what she said, just that I stopped crying.

Today, I often think about that experience while reading American news filled with shootings. People killing each other in the streets like in the old cowboy movies.

Yes, I wanted to be an American cowboy as a kid. But a robin sacrificed its life to teach me a deeper lesson, a bigger lesson about the sanctity of life.

America taught me mountains

Tatoosh Range of Cascade Mountains

On my first backpacking trip in the 7th grade, I was hooked on big mountains. At first, it was California’s High Sierras, then Oregon and Washington Cascades, then the Himalayas and the Andes.

Found Pencil: The beginnings of Human Civilization

Napa, California. Second grade.

I arrived to my first American school with a dozen English words in my mouth and my only possession clipped in my pocket—a mechanical pencil.

During recess, we kids played in the neighboring field. One day back in the class, still sweaty from running, I felt my shirt pocket for the pencil. Gone. I felt for it again. Still gone.

Did I actually cry? (Surely I hadn’t learned yet that American boys don’t cry) or just looked like a sack of sadness staring at my empty pocket. Yet somehow the teacher understood a Universal Language without words. She stopped our lessons. Marched the entire class out to search the city block size field of dry knee-high weeds.

Searching. Searching. “Found it,” yelled one of the kids. I didn’t know his words, But I understood what he said. For me, he had found the long lost sheep.

Many years later, I read a lecture by anthropologist Margaret Mead. A student asked what was the first sign of civilization. Agriculture? Clay pots? Grinding stones? iPhones?

“No,” Mead replied. In fact, it was a broken femur that had healed. That was evidence that someone tended that person to recovery, to survival. “Helping someone else is where civilization starts,” according to Mead.

Thank you second grade teacher, my cultural femur healer. Besides English, you taught me the beginnings of human civilization: kindness.

No problem. First we drink vodka.

Moscow international airport Lufthansa flight 1374 from Frankfurt to Moscow.

In my thirties, I headed to Latvia for the first time. But my flight out of Portland, Oregon was delayed. Then another delayed flight. Eventually I ended up in Moscow. That was Soviet Moscow in the late 1980s. No visa. No papers. And I didn’t speak Russian.

Like a wide-eyed lost immigrant I wandered the barely-lit airport searching for any mention of my Riga flight. Nothing.

Two cigarette-smoking guards with Kalashnikovs appeared, asked for something, probably my visa. I shrug. Riga?

They marched me off to a small windowless room stuffed with cigarette smoke. A military officer sat behind the metal desk. He sized me up, dismissed the two guards, started speaking. I just stood there, “Net russkogo.” I don’t speak Russian. So I tried English, then Latvian, finally German. “Ja wohl.”

After I explained how I ended up in his office, he casually waves his hand: “No problem. Sit down. First, we drink vodka.”

After several shots—it was actually good vodka—some casual 30 minute chat about family, women and life, the colonel arranged for a guard to drive me to the separate local airport for the Riga flight. (Later I learned that the KGB commonly used vodka to loosen suspects during interrogations.)

In the cool early morning hours, with a sigh of relief I climbed the stairs onto Aeroflot flight 2093. No assigned seats. The back of the plane looked like an immigrant’s steerage. A pile of cloth-wrapped parcels filled the isle. Sat down, pushed on the seat in front of me. It fell forward. The plane took off while people still wandered the isle. I fastened my seat belt.

Finally, I was headed for the first time to Latvia. I felt like an immigrant.

Homecoming

When I got off the airplane, I wondered what it would be like? So this is Latvia?

How I found the other door

Sigulda, Latvia 1991

Early one morning in Sigulda, I wanted some milk. So I did what most Latvians had done for 50 years of Soviet occupation. I stood in line. Waiting.

Finally got in. There in front me stood the brightly lighted dairy case: empty. Nothing but cool air.

“Where is the milk?” I asked.

“Gone. Deficits.” explained the uninterested clerk, droning like I should have known that.

A week later while enjoying too much beer and vodka with a family in Kuldiga, I shared my milk woes.

“Ah, I happen to work at that very store,” explained one of the women. “Next time come to the other door.”

“The other door?”

“Yes, go around the corner, to the back of the store. Knock. There you can get all the milk you want.”

Ah, so that’s how the Soviet system works. Two doors: the front door and the other door.

Memories meet reality

Near Vilpulka, Latvia 1989-2025

Are memories sometimes bigger, or at least different, than reality?

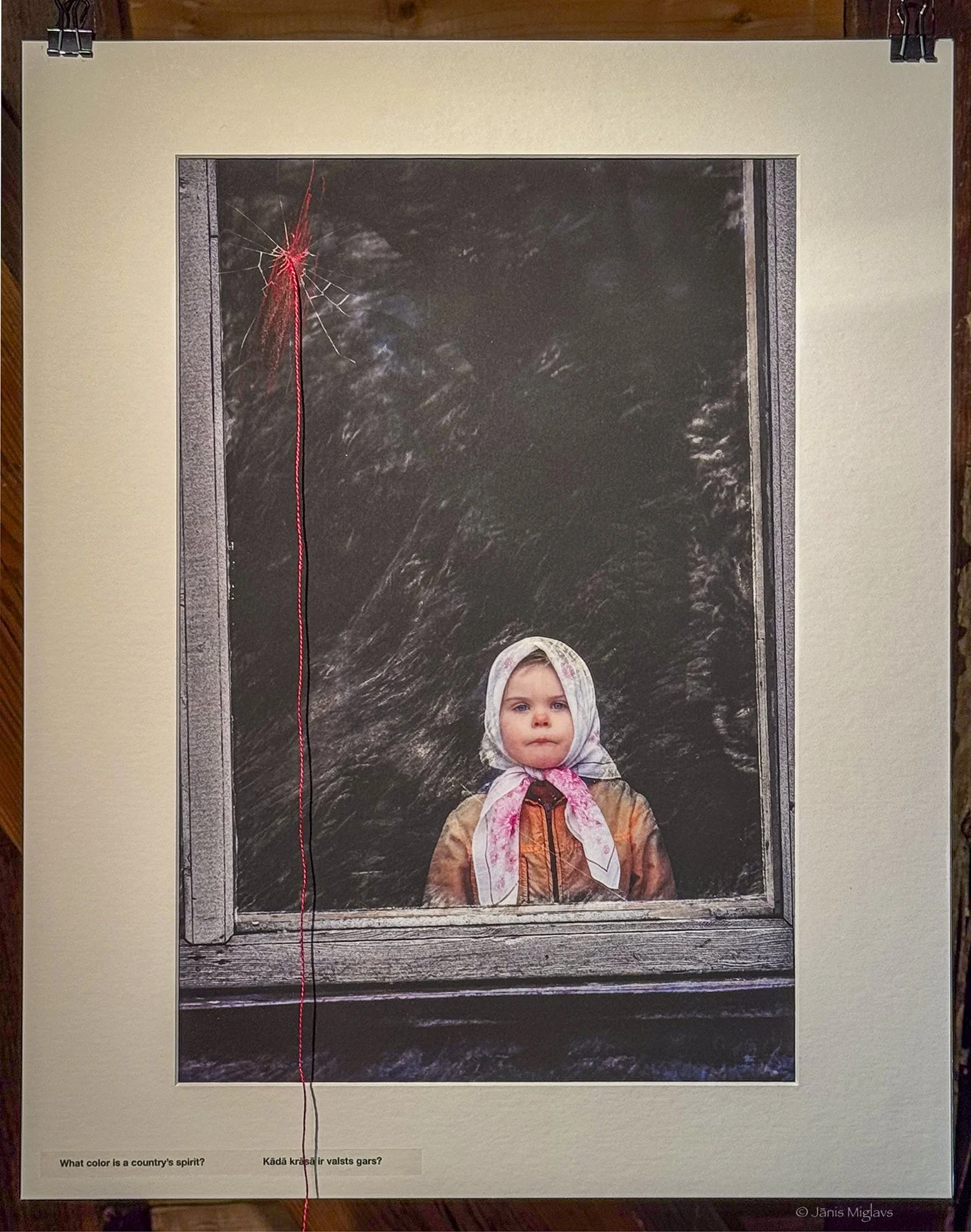

What color is a country’s spirit?

Sigulda, Latvia 1991

My first trips to Latvia were during Soviet occupation. Everything seemed covered in soot grey. I saw this girl in Sigulda staring out the window and wondered the color of her future.

Jānis, he could have shot you on the spot!

Vilpulka, Latvia 1991

October 24, 1991. In a tiny smoke-filled room, I sat across a table from the former Soviet collective (kolkhoz) director. Newly enacted repatriation laws now allowed me to reclaim the family farm—Namnieks—my parents fled almost 50 years before.

“But it belongs to the collective (Kolkhoz),” declared the director with gritted teeth, slamming his fist on the table to emphasize each word. “I have already given the farm to someone else. I can give it to whomever I want.” Mentally I repeated, he can give it to whomever he wants.

I arrived a naive American, used to freedom and the rule of law. So I protested. Showed the director and commissioner the paperwork with the official seal of freshly independent Latvia.

The air went dead quiet. For four hours we dueled with words. Back and forth. For me, no compromise. This guy was a hangover of a system that forced my parents to flee for their lives. Now I was fighting to reclaim something taken from my parents.

Finally, he had no choice in newly independent Latvia. He conceded, “It’s awkward for me to go back on my promise.”

While Latvia and the new laws had won, locals still lived in the dark Soviet hangover.

“Janis, he could have shot you on the spot,” Velta shouted, when I told her of my experience. This gentle woman bent by a life of toil was my mom’s best friend growing up but decided to remain in Latvia when my parents fled.

Her words hit like a reality slap on my face. Obviously, I didn’t fathom the power the diminutive man I faced once had.

Amazingly, as I write this in mid March 2025, I recall this story as America’s new president acts as if he can do as he wants. The exact sentiment I heard the Kolkhoz director tell me 34 years earlier. And now, I can’t help but ponder how my parents fled, knowing what was to come.

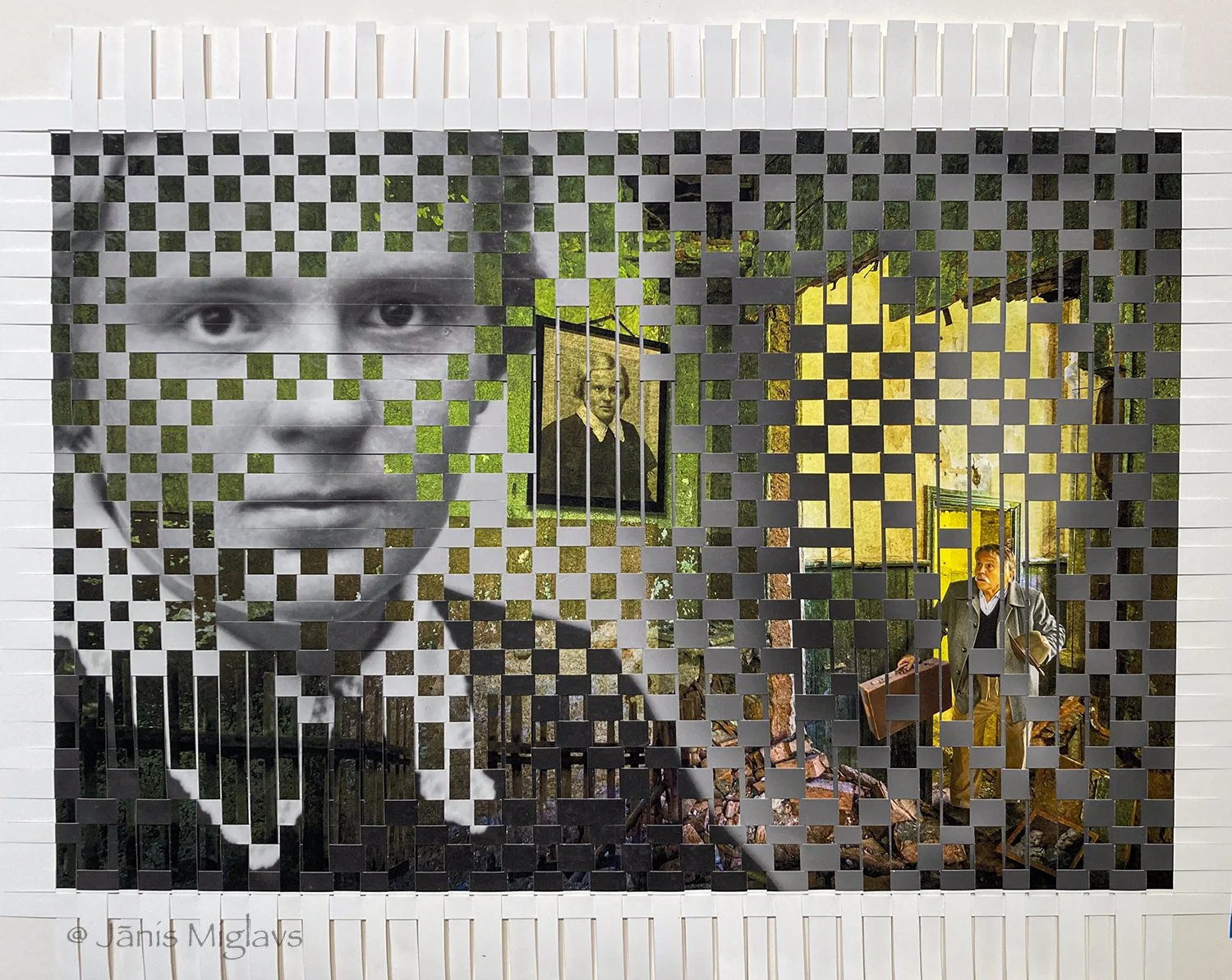

Mom memory

Weaving of two separate photographs in memory of my mom.

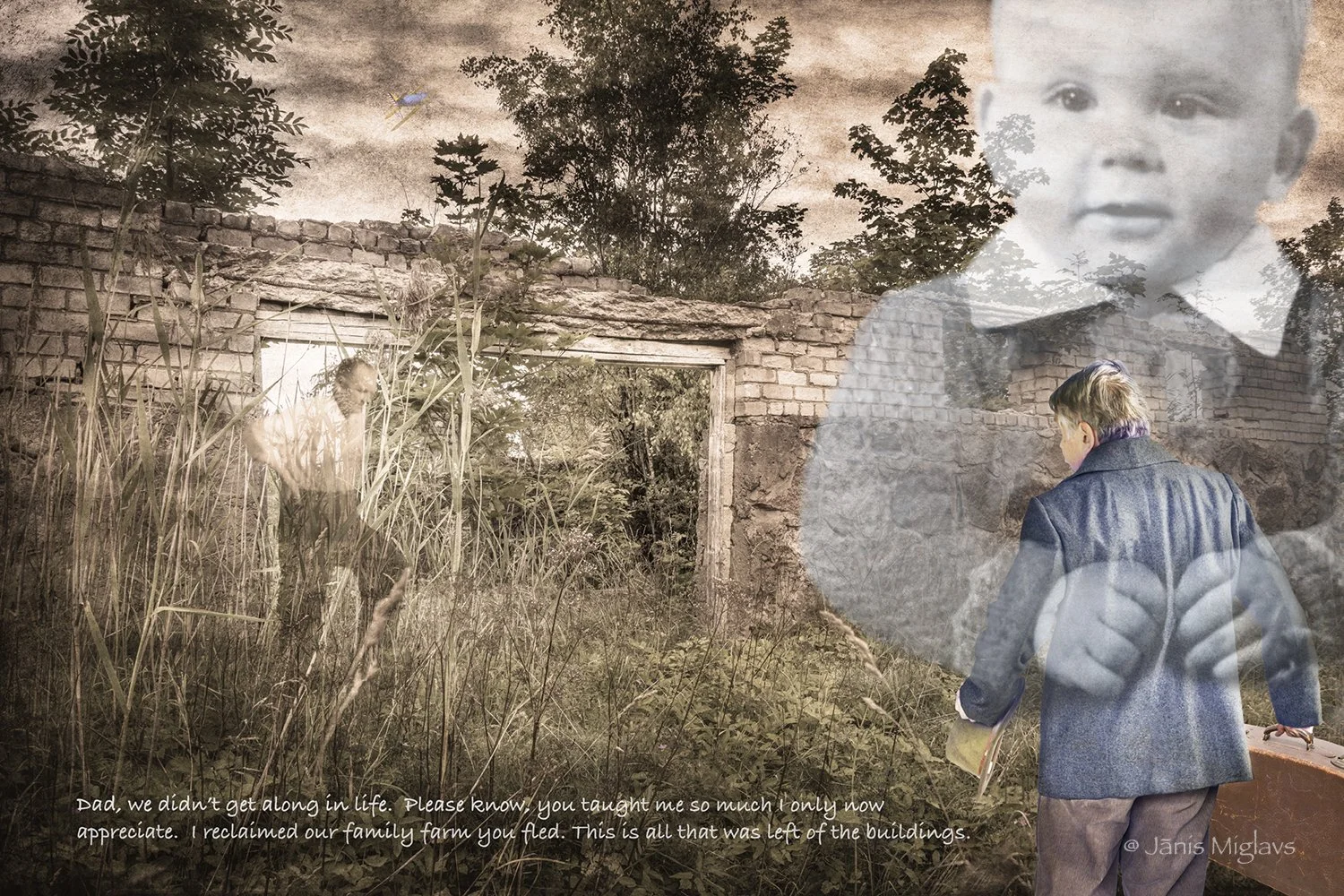

Oh, so many regrets and loss

Namniekos, family farm remains, near Rūjiena, Latvia

Dad, we didn’t get along in life. Please know you taught me so much I only now appreciate.

I reclaimed our family farm you and mom fled. This is all that was left of the buildings.

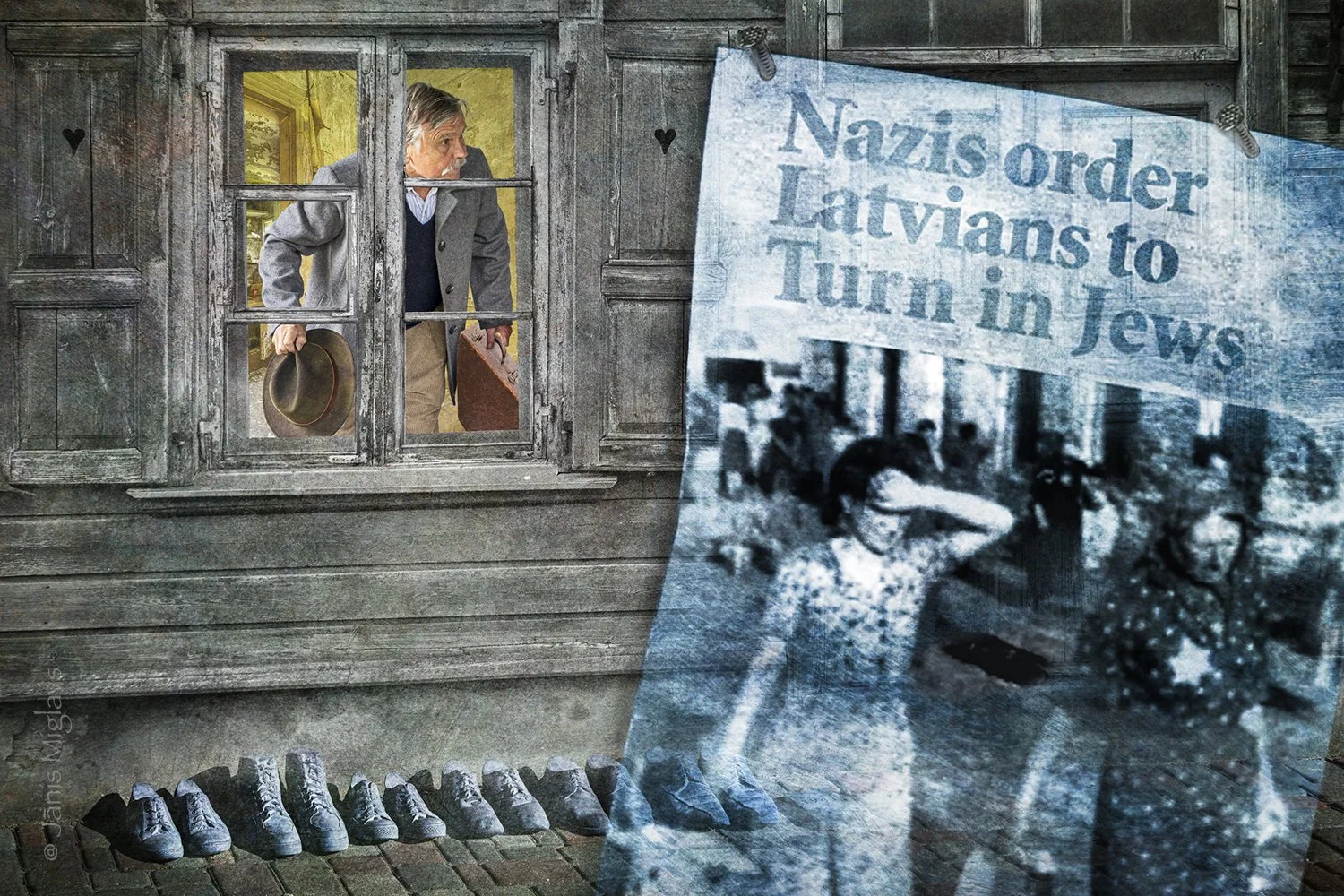

Silent Shoes

Highway I-24 in Tennessee, USA and Raina Street in Cesis, Latvia

“I shot a niggers foot off last night,” boasted the white driver as I got into his car. He was one of my rides as I hitchhiked across America.

Years later, in front of the old wooden apartment house I had booked in Cesis, Latvia, I noticed a tidy row of concrete shoes lined up on the sidewalk. A pair of baby shoes, three pairs of older kid’s shoes, one teenager, mom, dad and a grandparent.

They were Jewish. A Rabbi and his entire family.

All killed, along with some 70,000 other Latvian Jews starting in 1941. All murdered by German troops and fellow Latvians.

They once lived in the very apartment where I would sleep for the next week. They walked the very floor I would walk.

I kept staring at the little grey shoes, a silent reminder of that family. And it’s hard to walk many blocks in Cesis without seeing rows of silent shoes lined up in front of homes. Baby, teen age, adult, grandparent’s shoes.

My mind wonders back to my hitchhiking experiences. How many black and other minorities’ silent shoes would be lined up across America?

But honestly, would I have stayed silent in Latvia? Am I silent in America? And what happened to what people often repeat: “never again”?

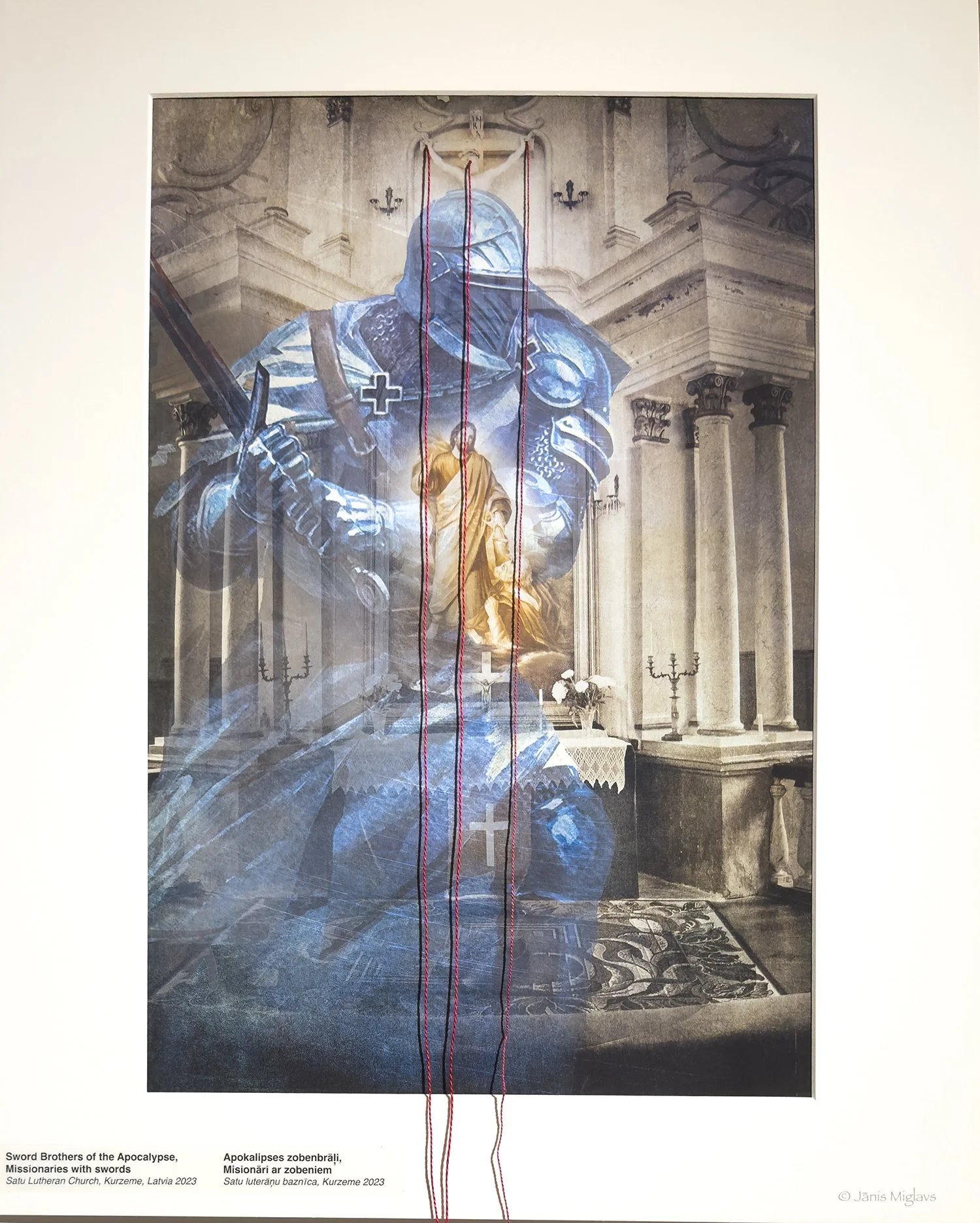

Black shoes, Brothers of the Sword and kindness

Latvia 13th century Napa, California 1950s

Starting sometime early in the 13th century, the Catholic Pope sent the Brothers of the Sword to convert nature-loving Latvian pagans to Christianity. These well-armed missionaries used pretty harsh conversion methods: believe in Christ or die by the sword.

More than 750 years later, without words or a sword, Mr. Greenfeld taught me about Christianity. He and his family helped my parents, sister and I first settle in Napa California.

They helped us find a home. I still remember Mr. Greenfeld helping me sign up for school, make sure I had decent clothes and a real bed. And he gave me my most valuable possession, a mechanical pencil. No preaching. No sword.

“By our love, the divine may be reached and held. By force only blackness can be seen.”

An anonymous 14th century author of A Guide to Clear Living.

PS. As a young kid, my one sacrifice to Christianity: wearing black shoes to church. They were always too tight.

Am I a visitor, a native or what?

Many places throughout Latvia 1989-2025

My youngest son and I were about to board the double decker Hop On Hop Off Riga tour bus. I asked for a Latvian citizen discount. Why not? I always ask for discounts. And I do have a Latvian passport. Yes, we got a discount.

As we passed the Freedom Statue, tears rolled down my cheeks. I recalled my many visits during the late Soviet period and early independence. All of the fierce discussions about who should be given citizenship. Should Latvian language be required?

But I’m also an American citizen. An immigrant. My parents raised me in Napa, California. I moved to Oregon with my own young family, developed a successful business as a writer and photographer.

Looking back, I still don’t fully understand what kept drawing me back to Latvia. Repeatedly. Twice in 1991. There was something about the people’s raw grasping for independence, for freedom. Latvian flags pasted on everything from delivery trucks to jacket lapels.

Caught up in that wave, I wondered how could I help?

Independent Latvia’s economy wallowed in shambles. Through my American photography business, I knew how to promote tourism. So in 1992, I went to the new Latvian tourist director with an idea.

Help me travel around Latvia to take scenic photographs to sell the castles nestled in forests as a travel destination.

Since it didn’t cost him anything, he sent me off with a smoke-spewing Volga and three beautiful ladies with traditional clothes. Now 33 years later, I saw one of those photographs still used in a major travel guide.

Yet after dozens of trips and adventures, I still wonder am I a Latvian visitor, a native or what?

Mindful of my own footprints

Latvia, America, Europe, Africa, South America

We were given this world by people who had less than we have. What can I learn from them?

What do I hear my parent’s grandparents telling me that I can pass on to my grandchildren and their grandchildren?

What foot prints do I want to leave for those who follow?

We all have five fingers

Konso, Ethiopia 2001